Uvaŋa atiġa Asiqłuq. Aapaga Sanguk. Aanaga Aileen-mi. Aakaga Ahnakosoklu suli Mary-milu. Avauraġa Fred-milu suli Edgar-milu. Qawiaraġmiuruŋa.

My Iñupiaq name is Asiqłuq. My parents are (the late) Aileen and Clifford Sanguk Topkok (from Teller, Alaska). My grandmothers are (the late) Gussie Ahnakosok Topkok and Mary Tweet. My grandfathers are (the late) Fred Topkok and Edgar Tweet. I am a person of the Kauwerak from the Seward Peninsula.

(An authentic Iñupiatun introduction.)

My white fox name is Sean Topkok, and I prefer to be called Asiqłuq. The Iñupiat1 used to have only one name (Craig 1996). When Elders ask us our Iñupiaq name, they know our family tree just by that one name. When the missionaries and first teachers came and were documenting names, they wanted to include first and last names. Since Iñupiat usually had only one name, missionaries assigned another name. In many villages, for an Iñupiaq to get another name, missionaries required that person to be baptized. The price for a baptism was one white fox pelt. Hence, when one refers to an English name, it is also referred as a “white fox name.” I am Iñupiaq, Sámi, Irish, and Norwegian. My father was Iñupiaq and Sámi, and his first language was Iñupiatun (the Iñupiaq language). My mother was born and raised in Teller. My paternal grandfather, Fred Topkok, was a reindeer herder. I was born and raised in Spenard, Alaska. I am still learning the Iñupiaq and Sámi languages, and my family speaks English and Norwegian at home. My wife and I have three sons and currently one grandson. I am the fifteenth Iñupiat to earn a doctorate degree and currently am a faculty member in the School of Education at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF).

The above personal introduction contains key elements for a cultural atlas, a way of documenting cultural heritage. The key elements in my introduction identify iñuk (myself as a person), iḷagiiñiq (family relations), nunaaggiq (village or community). This article is a case study of my active involvement in two university courses to collaborate with students and community members to document their place and heritages; improve teacher retention by active involvement through course activities; and provide preservice teachers an opportunity to visit a remote Alaskan village and gain firsthand knowledge from first-year teacher experiences.

Literature Review

In contemporary times, the number of Indigenous scholars researching Indigenous and Western paradigms is increasing, critiquing how Western paradigms tend to be inadequate for Indigenous research and education in their current forms (Dunbar 2008, Jacobs 2008, Kovach 2009, Smith 1999, Topkok 2015, Wilson 2008). Through their initiative, other Indigenous communities worldwide are inspired to grow their own Indigenous scholars. The concept and process of “growing Indigenous scholars” coincide with Marie Battiste’s statement (2013): “Indigenous people are also moving beyond critiques to address the healing and wellness of themselves and their communities, to reshape their contexts and effect their situations, and to create reforms based on a complex arrangement of conscientization, resistance, and transformative action” (69). This theoretical framework connects the Indigenous researcher to existing generational knowledge and nurtures Indigenous scholars to identify their Indigenous knowledge as a valid source. Likewise, Western scientists recognize Indigenous knowledge as authentic: “Numerous authors have demonstrated the profound sense of awareness and place-based knowledge that traditional hunters and their communities have about the dynamic changes in their local environments (Robards et al. 2018).

When dealing with preservice and teaching education, cultural rigor should be taught at the same level as academic rigor. There is an increase of documenting Indigenous methodologies, incorporating Indigenous epistemologies, ontologies, and theoretical frameworks (Dunbar 2008, Jacobs 2008, Kovach 2009, Meyer 2001, Smith 1999, Topkok 2015, Wilson 2008). More papers and books are being written about Indigenous methodologies and cultural values by Indigenous scholars for upcoming Indigenous students. Indigenous scholar Marie Battiste (2002) writes: “As a concept, Indigenous knowledge benchmarks the limitations of Eurocentric theory–its methodology, evidence, and conclusions–reconceptualizes the resilience and self-reliance of Indigenous peoples, and underscores the importance of their own philosophies, heritages, and educational processes” (5). Indigenous theoretical frameworks are important because they offer an Indigenous perspective on research for academia. Our research with our Iñupiat cultural values resonate locally, nationally, and internationally for more Indigenous scholarly resources and will contribute to this growing literature.

Margaret A. Cargill Foundation Funding

Margaret A. Cargill Foundation (MACF) is a private foundation that came into existence upon the donor’s death in 2006 and focuses on several domains, including Native Arts and Culture. The MACF description notes that a “…focus in Native American and folk arts and cultures supports the intergenerational transference of artistic skill and knowledge, where skills and meaning are rooted in longstanding traditions defined by local communities of practice” (MACF n.d.). Each domain requires that three institutions collaborate: a university, a school district, and a nonprofit arts organization. MACF identifies one institution to take the lead and distributes allocated funds over several years.

In 2015, my UAF School of Education colleagues with the North Slope Borough School District (NSBSD) were asked to be collaborators for an invitation-only MACF multiyear grant. The purposes of the grant were to improve the quality of K-12 teachers in Alaska and the graduation rate of qualified students from high-quality preservice teacher programs in Alaska.

NSBSD took the lead for the Supporting Iñupiaq Arts and Education grant, and contacted the UAF School of Education to partner as the university collaborator. Cultural Elders and culture bearers were identified through the Alaska State Council on the Arts, the nonprofit collaborator. All the directives were implemented through the lead organization, the NSBSD, and agreements were formalized.

Under the agreement, the School of Education faculty collaborated with NSBSD in developing and delivering a course that meets Alaska Department of Education and Early Development requirements for three credits in multicultural education.

Cultural Atlases as a Pedagogical Strategy

I have successfully created a new catalog course, Cultural Atlases as a Pedagogical Strategy, which I taught as a Special Topics course in 2006. The NSBSD agreed that the course satisfies the above agreement, and it is recognized by the Alaska Department of Education and Early Development as a multicultural endorsement, one of two requirements needed to teach in Alaska. The other required endorsement is Alaska history. It is now a catalog course. The course description is also a cultural atlas definition, which may be an electronic living document or a written document for future teachers. Ideally, communities will have the opportunity to build and define their own cultural heritage further through a cultural atlas.

The Cultural Atlas course is divided into six modules. Each takes two to three weeks to complete. The modules are Creating a Story, Family Tree Project, Interviewing Elders, Community History, Place Names, and Bringing It All Together. I based the course on an analogy from a Tlingit culture bearer who shared understanding one’s cultural heritage with me. He said a cultural heritage is like a forest. You have one single tree, yourself, which needs to be healthy and strong. The surrounding trees are your family members. The whole forest is your community (Topkok 2010). Students are encouraged to explore various Western and Indigenous methodologies to develop their local cultural atlas. The Cultural Atlas course is a method for communities and students to document their own cultural heritage. Students work with Elders, families, and community members to share their personal stories. They identify their genealogy, interview culture bearers, and archive their community history. The students also identify place names, including Indigenous names of sea and landmarks before colonization.

The following are the modules I require of graduate students, who are usually teaching in rural Alaska, to first do for themselves (creating an example to show their students), and then to teach their students.

Module #1 (My Story). Your assignment for this module is to guide the student through a process in which you will develop a preliminary outline of what a story of your family might look like and then develop an outline of what the story of your community might look like. This is your own creation, so your family and community story should have its own unique quality. When the outline is complete, we will set up a website where you will begin to upload the information you have gathered as the first installment toward your “Cultural Atlas.”

In my introduction, I state who I am and who I am named after. This assignment allows K-12 students an opportunity to inquire how they were named, whether it be their Iñupiaq name or their other name. Rachel Craig (2011) writes very helpfully about Iñupiaq names. This applies to other groups, Native and non-Native, since we all have a story to share about who we are.

Module #2 (Family Tree). When you are gathering and inputting your data, be sure to include Native names where applicable, along with the origins and/or translation, kinship terms, and pictures or any multimedia available, all of which will be examined and critiqued as it relates to issues raised in the readings. Please include all information available–you can decide later what can and cannot be shared. When completed, your family tree will be added to your Cultural Atlas website, along with a journal in which you describe what you learned from the process.

Knowledge of one’s family tree is a cultural value in many Alaska Native groups. Kinship terms vary in Alaska. Yup’ik kinship depends on the gender of the person.2 This assignment allows K-12 students an opportunity to know who they are related to. I encourage students to utilize kinship terms from their heritage language. This is educational for Native and non-Native students, allowing them to get to know who their ancestors are.

Module #3 (Tea with Elders). Elders are our culture bearers. They hold deep-rooted knowledge about who we are and where we come from. Much can be learned from listening to an Elder, though it requires respect and patience. Therefore, you must do a chore for an Elder and commit to having tea or coffee with them. It is important to pay attention not only to what Elders say, but also when, where, and how they say it. When possible, tea should take place in the Elder’s home or a natural setting in the community. (The Aleut/Alutiiq Cultural Atlas provides an example of groups of Elders sharing their knowledge at http://ankn.uaf.edu/CulturalAtlases.)

I have worked with many Elders statewide, nationwide, and internationally. There are many Elders who state they are tired of people coming to them just to gather information. Doing a chore and having tea or coffee with an Elder establishes a relationship and trust. Often, spending time with an Elder creates an intimate relationship lasting a lifetime.

Module #4 (Community History). You should choose one of the examples from the readings (or develop a focus area of your own) and begin documenting information about the history of your community, including the contributions of plants and animals in the surrounding environment to the livelihood of the community. Your assignment is to prepare an initial compilation of community history information for a Cultural Atlas, keeping in mind that this can become more detailed and elaborated as an ongoing project in your school and community. (The Marshall Cultural Atlas is an example of this project, see http://ankn.uaf.edu/Resources/course/view.php?id=16.)

Figure 1. Graduate student Celina Swerdfeger pointing to a trading post during a culture camp.

Photo by Asiqłuq.

Module #5 (Place Names). Your task will be to develop an interactive multimedia map of your surroundings in which to document the place names of the local area. You should prepare a map and an initial compilation of place names for your area to be added to the local Cultural Atlas. (The Angoon and Kake Cultural Atlases are great examples of Place Names, see http://ankn.uaf.edu/CulturalAtlases.)

One year during this course, residents voted to change a North Slope village name from Barrow to its original place name Utqiaġvik. Elders expressed a concern about community members getting lost and perishing. One solution they suggested is to emphasize teaching significant landmarks that have place names. In Figure 1, Celina Swerdfeger points to an old trading post built long before Western contact where Iñupiat would gather to trade, dance, and tell stories.

Module #6 (Bringing It All Together). The final project to be completed over a period of three weeks is to consolidate your Cultural Atlas framework and refine your website to upload and organize the information you have assembled. You should then prepare a how-to guide that you will present to the rest of the class incorporating the Cultural Atlas content and strategies you have developed and describing how you would put the academic, cultural, and technological skills you have learned to use in working with future students in your school.

Mapkuqput Iñuuniaġniġmi—Our Blanket of Life

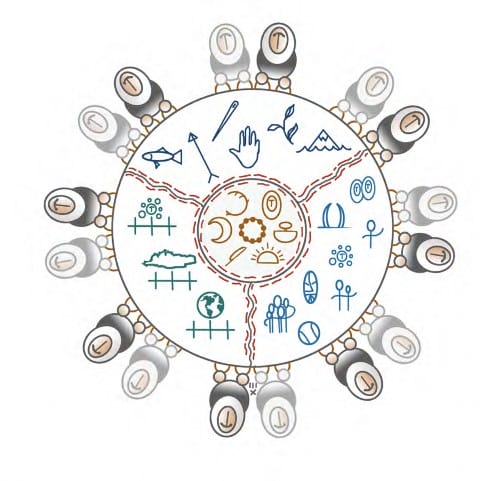

In 2010, NSBSD adopted an Iñupiaq Learning Framework (ILF) called “Mapkuqput Iñuuniaġniġmi—Our Blanket of Life” (see Figure 2).3 Local educators and community members in the school district developed this framework and continue to add lessons and Iñupiaq assessments to meet cultural and academic rigor for their children. This Iñupiaq framework identifies knowledge and skills needed to be taught in their Iñupiaq curriculum based on Iñupiaq cultural values. They put each skill into four realms: Individual Realm, Community Realm, Environmental Realm, and Historical Realm. Each is tied and connected together with sinew, representing the Iñupiaq language and spirituality. The symbols on the blanket represent the North Slope Iñupiaq Cultural Values.

Figure 2: Mapkuqput Iñuuniaġniġmi—Our Blanket of Life.

Looking at the cultural atlas as a Pedagogical Strategy course and the ILF, one can see how the modules and realms complement each other (see Table 1). The NSBSD invited 25 first-year teachers to enroll in the Cultural Atlas course for this very reason. Since I am an Iñupiaq professor and familiar with the ILF, I could encourage the NSBSD first-year teachers to develop their school and community cultural atlases based on the ILF. Contemporary research shows teacher retention and attrition depend on how active teachers are in communities and how the educators teach through the culture (Kaden, Patterson, Healy, and Adams 2016).

Table 1. Modules and Realms

| Cultural Atlas Modules | Iñupiaq Learning Framework |

| My Own Story | Individual Realm |

| Family Tree Project | Community Realm |

| Interviewing Elders | Historical Realm |

| Community History | Environmental Realm |

| Place Names | Language and Spirituality |

The NSBSD invited 24 new teachers to take the course. Of the 24 teachers, 11 initially enrolled. Because of various personal reasons, six withdrew. The remaining five passed the course. One teacher wrote in a journal entry:

But what has come now is a deeper understanding that the person sitting [or] standing right next to me, even one that looks like me, may have a completely different orientation to life, upbringing, and deep ancestral history. With that we begin the journey!

This demonstrates the impact the course had on just one student. Others stated that they would make their local cultural atlas a blog, a first-year teacher’s manual, and a video series. I encourage students to draw on their strengths to develop their own cultural atlases. One chose blogging (edited for anonymity):

One of those is my Cultural Atlas blog, created for this course. I had vast difficulty trying to upload documents and photographs to [a website] and so was advised to use my strengths in resolving the issue. My response was to create a blog specific for the course where I could post my completed assignments in a written and visual manner that I was greatly familiar with and which would allow both my professor and fellow students to read and view (additionally, as it is a public blog, random Google searchers may find themselves reading one or two of my posts) (personal communication).

This student flourished with their blog, uploading multiple photos of animals, the community, their classroom, and much more. They wrote about various experiences with community members and Elders.

Another student concluded a paper about Interviewing Elders (edited for anonymity) by writing:

In my short time living in the village, I have been fortunate enough to enjoy participating in both hunting and fishing. I will continue to enjoy the fishing and hunting in this vast Arctic paradise, calling upon my own expertise as a fisherman and what little experience I have as a new hunter. More importantly I will call upon the knowledge of the Elders and those in the community who possess a wealth of knowledge on both hunting and fishing, a deep and seemingly endless knowledge that enables them to live at the top of the world in a landscape whose extreme climate is contrasted by its extreme beauty (personal communication).

I have heard several stories about a new teacher arriving in remote Alaska, not stepping off the plane, and leaving the community. The above student’s experience shows interaction with Elders and community members, visiting the environment, and acknowledging the sense of place as extreme yet beautiful. This is not an isolated experience. Another student wrote (edited for anonymity):

[My partner] and I have a great relationship with this person [an Elder] already but speaking with her about this place and hearing her ideas that are not shared each day was a great experience. She shared with me a dream she had the night before we visited with her, where I showed up and asked if I could sleep there. She told me yes, that I could. It meant a lot to me that I ended up somewhere in her unconscious thoughts, as she is special to me, and [my partner] as well (personal communication).

Culture Camp

As requested by NSBSD, we solicited and brought a future teacher to one of the Culture Camps. Another class I teach is Alaska Native Education, a required course for students enrolled in the Bachelor of Arts in Education degree program at UAF. I invited all the preservice teachers in my class to visit a remote village for a culture camp experience, paid through the MACF grant. (More preservice teachers were interested in attending, but schedule conflicts made it impossible.)

Figure 3. Kayuqtuq (fox) visits the culture camp.

Photo by Asiqłuq.

I was able to travel with one student, Celina Swerdfeger, to one of the NSBSD villages. We were welcomed by school personnel and introduced to the staff. We met with an Elder and the culture camp coordinator to go over the schedule for the two-day visit. There happened to be a potluck scheduled the evening we arrived, giving us an opportunity to meet community members, children, school staff, and borough personnel. We were lucky to meet the first female whaling captain, who successfully fed her community with the whale who gave itself to her. After the community potluck, my preservice student spent the rest of the evening visiting with first-year teachers. Celina and the first-year teachers were enthusiastic about talking with each other. The first-year teachers were sharing their experiences and asked if Celina was interested in teaching in the NSBSD. Celina was curious to experience more about the place. The following day, community members and the culture camp coordinator planned to take us and the first-year teachers on an hour-long snowmachine ride (some people refer to snowmobiles as snowmachines) out of the village to experience ice fishing.

There were several first-year teachers in this remote village. This was the first time for many to be on a snowmachine. Community members with snowmachines took all of us out of the village onto the frozen river. All snowmachines were pulling wooden sleds for riders and equipment. We went for a half an hour, warmed up, then continued to the mouth of the river. At the ice-fishing spot, nets were placed between two holes to catch iqalusaat (Least Cisco) fish. There were several nets set for us to pull out of the ice and take the iqalusaat out of the nets. At our last fishing spot, a kayuqtuq (fox) decided to pay us a visit. In Figure 3, you can see the preservice teacher bending down to take a photo and how the kayuqtuq did not show any fear but kept its distance. A community member tossed it an iqalusaaq as a gift. We then returned to the village, and the Elder and culture camp coordinator had to fly out that late afternoon. The preservice teacher and I left the following morning. My student stated this was an experience they will never forget and encouraged other students to visit a remote village if given the opportunity.

Conclusion

While the initial funded program is no longer being offered, it is clear that the participating first-year teachers built relationships with their communities by participating in the Cultural Atlas course and the culture camps. These opportunities provided firsthand experiences with preservice teachers in the Alaska Native Education course. I feel this was a great partnership and look forward to possibly working together in the future for Alaska’s education.

The NSBSD Iñupiat cultural values were observed when the first-year teachers and preservice teacher participated in the Supporting Iñupiaq Arts and Education project In Table 2, the left column lists the NSBSD Iñupiat Cultural Values, while the right column shows how the cultural value was observed during this interactive experience.

Table 2. NSBSD Iñupiat Cultural Values and Interactive Activities4

| NSBSD Iñupiat Cultural Values | Interactive Activity |

| Avanmun Ikayuutiniq (Helping Each Other) | Students learn from each other while they actively participate in the classroom or at a culture camp. |

| Avilaitqatigiigñiq (Friendships) | Students going through a cohort develop friendships that last a lifetime, encouraging each other to try new things, offer support, and maintain relationships. |

| Iḷagiiñiq (Family Relations/Roles) | Community members are actively involved and understand their various roles in the village. |

| Iḷammiuġniq (Creating Friends) | The culture camp allows an opportunity for preservice and current teachers to engage with community members and create relationships. |

| Igḷutuiguniq (Endurance) | Cultural activities happen year-round. It takes perseverance to maintain a necessary subsistence lifestyle. |

| Ikayuqtigiigñiq (Cooperation) | Supporting Iñupiaq Arts and Education was a collaborative project involving community members, educators, culture bearers, and administrators to make it a positive experience. |

| Irruaqłiġñaiññiq (No Mockery) | Respect is highly valued for any cultural heritage. We do not mock people nor their knowledge systems and beliefs. |

| Kipakkutaiññiq (Respect for Human, Animals, Property, and Land) | During the culture camp, we did not disturb other fishing spots, looked out for each other’s safety, fed the kayutuq, and did not disturb the water, land, or air. |

| Mitaallatuniq (Sense of Humor) | Humor is a shared Alaska Native cultural value. Humor allows us to practice humility, knowing when we make a mistake we should not take it too personally. |

| Nagliktuutiqaġniq (Compassion) | While the community members invited others to their fishing spot, iqalusaat was shared to show compassion. |

| Nakuaqqutiqaġniq (Love) | An Elder expressed to me, “Everything we do, we should do it with love.” Love is reciprocal, which is a universal cultural value. |

| Piḷḷaktautaiññiq (Gentleness) | As we were taking the iqalusaat out of the nets, we did so gently to show respect to the animal spirits. |

| Piqpakkutiqaġniq Miqłiqtunun (Love for Children) | The culture camp and the cultural atlas assignments help the children better understand who they are. |

| Pitqiksiġautaiññiq (Honesty) | Each cultural heritage group has its own cultural protocols. Honesty allows us to learn and respect the Indigenous people who first came from the land. |

| Qiksiksrautiqaġniq (Respect for Others) | Not all communities welcome new teachers. Not all new teachers understand village dynamics. Respect for others helps build relationships. |

| Qimmaksautaiññiq (Patience) | It takes time for teachers to feel comfortable with a community and for community members to get to know new teachers. |

| Siġñataiññiq (Sharing) | Living in remote Alaska can be unforgiving. Therefore, it is imperative to share, whether it is something material or intangible. |

Students work with their communities to determine whether to share their cultural atlases with the public, depending on the cultural and intellectual property rights that communities have established. There are some examples of shared cultural atlases available at the Alaska Native Knowledge Network website (http://ankn.uaf.edu/NPE/oral.html). Some communities elected to share but want the general public to agree to the Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge, making the cultural atlases password-protected.

One of my students from the Alaska Native Education course earned her teaching certificate and wrote about her experience in rural Alaska:

Anybody who has taken a course with Dr. Topkok knows that he has a passion for education, especially for the underserved Alaska Native populations across the state. He has a profound ability to advocate for the Alaska Native populations in both a powerful and respectful way. His course had a great impact on me as an educator considering a teaching career in rural Alaska. He was a great role model for the type of relationship teachers can have across cultural lines and the collaboration that can occur to improve the quality of education for students. When teachers new to the state ask me about the mandatory Alaska Native Education course, I always recommend they look to the UAF for a course with him (personal communication).

I continue to teach the Cultural Atlas as a Pedagogical Strategy and Alaska Native Education courses. I share the Supporting Iñupiaq Arts and Education experience with all my students, letting them know of the positive collaboration, and allowing a glimpse into the benefits of working with community members, Elders, seasoned educators, and with other classmates.

“Uvaŋa atiġa Asiqłuq. Aapaga Sanguk. Aanaga Aileen-mi. My Iñupiaq name is Asiqłuq. My white-fox name is Sean Topkok. I am Iñupiaq, Sámi, Irish, and Norwegian.” Topkok is Assistant Professor at the School of Education in the graduate programs. His family is from Teller, Alaska, and is Qaviaraġmiu. His research interests include multicultural and Indigenous education, decolonization and Indigenist methods and methodologies, working with communities to help them document their cultural heritages, and community well-being.

Endnotes

- ‘Iñupiaq’ is singular or an adjective. ‘Iñupiat’ is three or more.

- See http://ankn.uaf.edu/SOP/SOPv4i2.html#yupik.

- For more about the Iñupiaq Learning Framework see https://www.nsbsd.org/Page/4542.

- Table is found at http://ankn.uaf.edu/ANCR/Values/inupiaq.html.

Works Cited

Battiste, Marie. 2002. Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education. Ottawa, Ontario: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

—. 2013. Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit. Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Purich Publishing Limited.

Craig, Rachel. 2011. What’s in a Name? In Sharing Our Pathways: Native Perspectives on Education in Alaska. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Knowledge Network, Center for Cross-Cultural Studies. Accessed August 1, 2018, http://ankn.uaf.edu/SOP/SOPv1i5.html#name.

Dunbar, Christopher. 2008. Critical Race Theory and Indigenous Methodologies. In Handbook for Critical and Indigenous Methodologies, eds. Norman K. Denzin, Yvonne S. Lincoln, and Linda Tuhiwai Smith. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 85-99.

Jacobs, Don Trent. 2008. The Authentic Dissertation: Alternative Ways of Knowing, Research, and Representation. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Kovach, Margaret. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Native Arts and Culture. (n.d.). Margaret A. Cargill Foundation. Accessed August 1, 2018, http://www.macphilanthropies.org/domains/arts-cultures/native-arts-cultures.

Meyer, Manu Aluli. 2001. Acultural Assumptions of Empiricism: A Native Hawaiian Critique. Canadian Journal of Native Education. 25.2: 188-98.

Iñupiaq Education. (n.d.). North Slope Borough School District. Accessed August 1, 2018, http://www.nsbsd.org/domain/44.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New Zealand: University of Otago Press.

Topkok, C. Sean. 2010. Iñiqpaġmiut Iñupiat quliaqtuaŋit (Iñupiat Urban Legends): An Analysis of Contemporary Iñupiat Living in an Urban Environment. Accessed August 1, 2018, http://ankn.uaf.edu/Curriculum/Masters_Projects/SeanTopkok.

Topkok, C. Sean Asiqłuq. 2015. Iñupiat Ilitqusiat: Inner Views of Our Iñupiaq Values. PhD diss., University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Kaden, Ute, Philip P. Patterson, Joanne Healy, and Barbara L. Adams. 2016. Stemming the Revolving Door: Teacher Retention and Attrition in Arctic Alaska Schools. Global Education Review. 3.1: 129-47.

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.