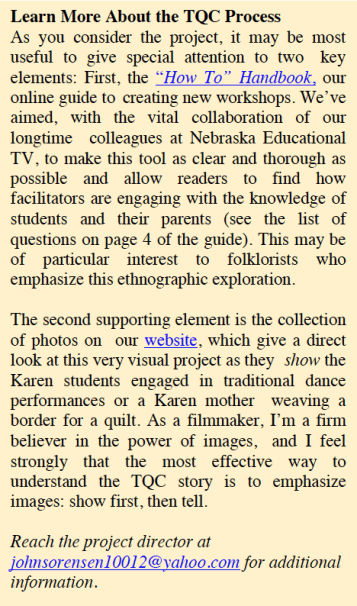

Africa on the Prairies

Peggie Hartwell’s story quilt tribute to TQC’s inaugural Sudanese workshop of 2008.

The Quilted Conscience (TQC) is inspired by the Nebraska born-and-raised social justice pioneer Grace Abbott who, in 1934, said, “Justice for all children is the high ideal in a democracy” (ii). Grace Abbott was a leader in the struggles to improve life for America’s children, immigrants, and women. As Chief of the U.S. Children’s Bureau, in a speech to the National Women’s Trade Union League, she noted, “It is a relatively few people who do accomplish things that must be done. It is a few who really care and keep steadily on the job, who finally convert the larger groups.” These two quotes are guiding principles of this project, which began in Abbott’s hometown of Grand Island, Nebraska, in 2008, the 130th anniversary of her birth in 1878 (qtd. in Sorensen 2008, 116).

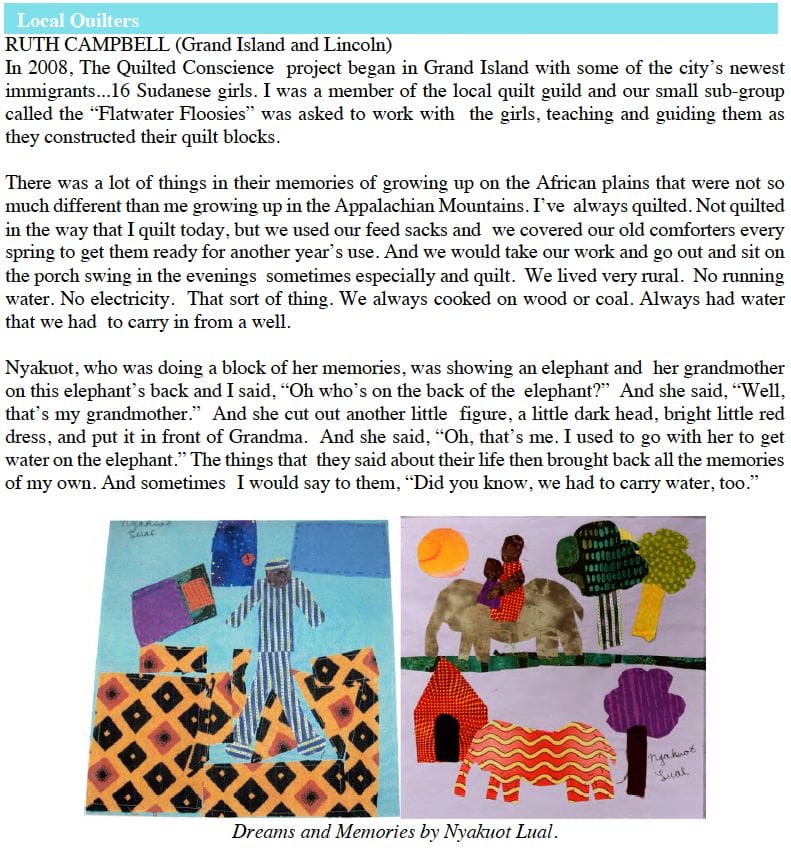

I am also a native of Grand Island, and I wanted to honor Grace Abbott in the spirit, and aspiring to the goals, of her lifelong work–not just a statue or a plaque–but something very alive that would touch the lives of the people for and with whom Abbott worked throughout her life. In discussions with my longtime friend and colleague, noted fabric artist Peggie Hartwell, the idea evolved to create an outreach project with female immigrant children who now live in Grace’s hometown. Considering Grace’s early work with Jane Addams at Chicago’s Hull House and Peggie’s long history of outreach in the schools of South Carolina, the notion soon evolved to offer an arts workshop to bring together diverse communities who otherwise might never meet: New Americans—refugees from the crisis in Sudan—and members of families who have been in the town for many generations. The initial goal was to help these two groups of Grand Islanders connect positively and creatively through making a mural story quilt to show and tell (through an accompanying “Quilt Key”) students’ stories of their “Dreams and Memories”–memories of life in Sudan and dreams for their lives in the United States.

The first step was to partner with the English Language Learner (ELL) Department of the Grand Island Public Schools to engage with an ELL teacher who could identify students interested in and (along with their families) likely to benefit from the experience. The next step was to connect with a local quilt guild whose members were interested in meeting their newest neighbors. We wanted them to teach basic sewing skills to the student artists and, perhaps more importantly, begin to learn for themselves something about life and culture in Sudan and the challenges of resettlement.

We hoped that along the way, both groups (as well as Peggie and myself) would find new ways to express their creativity and form new friendships. In the end, things worked out better and more unexpectedly than any of us could have predicted, including expansion of this one-time-only event into an ongoing project that has spread across the U.S., from Nebraska to South Carolina to Idaho.

TQC History

TQC’s achievements include a film (The Quilted Conscience) for public television and our rapidly expanding workshop and exhibition programs that have been developed and disseminated through extensive broadcasts and screenings of the film. Major TQC workshops have engaged with Sudanese American students (girls ages 10-18 of the Nuer, Nuba, and Dinka tribes); Karen American students (mixed- gender, ages 16-20, from Myanmar—also known as Burma—and Thailand); and groups of mixed ethnicity and gender from Iraq, Thailand, Venezuela, Myanmar, Guatemala, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. They have explored such questions as “Who am I? Am I African? Asian? American? Or African American or American Asian?” “What is meaningful and unique about my native culture?” “Why did my family come to this new country?” and “How can the lessons and ways of the past help me to be happier in the present and the future?” The young people develop their Dreams and Memories quilt images and find new ways to discover their past lives and potential futures.

We encourage partnering organizations to engage with adults from the students’ communities. For example, in our Sudan project we collaborated with a Nuba photographer and musician who was documenting the home-country life of Sudan where many relatives of the girls still lived. He brought his people’s visual art and music into our events, teaching his traditions to his new neighbors and the children of his own people. He and others discussed the challenges of keeping ancient traditions alive in modern times amid radically and rapidly changing circumstances, including such issues as “How is it possible for a culture that honors and is guided by its elders (i.e., grandparents, etc.) to survive in a land where none of those elders have immigrated?” For, as he said, “Even if you’re born into a fire, you don’t want to lose your culture.”

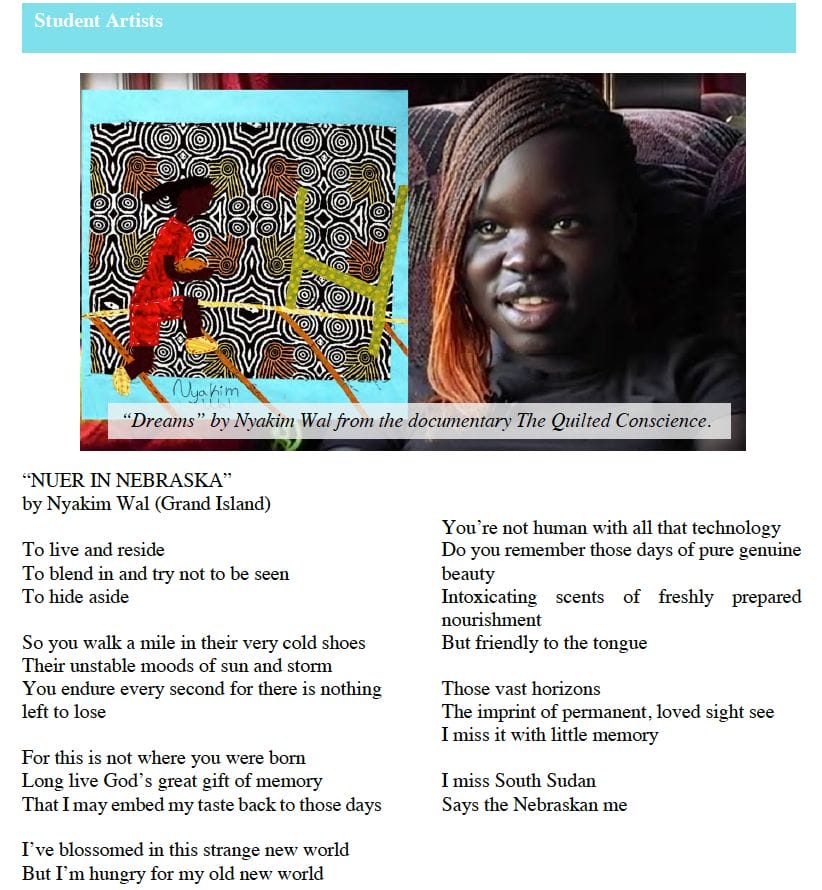

Some of the young quilters’ mothers weave a border for the quilt. Courtesy Peggie Hartwell.

In the first of our two Karen projects, we worked closely with a group of the students’ mothers who participated in workshops by creating a traditional weaving as a border for their children’s quilt blocks. In the finished quilt, the children’s artwork was literally embraced by that of their mothers. In the process, these women demonstrated the making of their extraordinary creations to American quilters who have described this exchange as life changing.

Workshops

In TQC workshops, refugee and immigrant students create Dreams and Memories quilt blocks for a large mural artwork, made to last many generations. The blocks are of cultural memories, with student artists answering the question “What is unique in who I am and in where I come from?” and honoring the traditions and heritage of their families and communities, showing what is best and most special to them in their pasts. The dream blocks answer the question “Who and what do I want to be in my new American life?” These images show what students aspire to in their American futures, ranging from hopes of being nurses and doctors to careers as lawyers or judges, football players or poets. TQC has completed 12 successful workshops with Sudanese and Karen refugees and other immigrants from around the world. A TQC- related Newcomers Quilt Program has won five blue ribbons and a red ribbon at the Nebraska State Fair. Also, the extended public exhibitions of the quilts offer opportunities for many people to discover the deeply moving arts and experiences of their new neighbors.

PERSPECTIVES

Next year is the 10th anniversary of TQC and to mark this milestone, I have assembled a collage of perspectives on the project, in the words and pictures of some students, quilters, educators, and community partners who have helped our work take root, grow, and evolve.

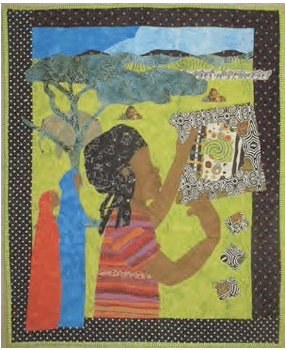

NYAKIM WAL (Grand Island)

I was born in Ethiopia in Africa. I was five when I left. It’s like a blur really ‘cause I was little. I can’t remember. We first came to Texas–Houston, Texas. And then we moved to Omaha. And then we moved to Norfolk. And then we moved here to Grand Island. I have friends throughout the community. I have friends that are white. Some that are black. And that are Nuer. I’m “mixed” when it comes to friends. Unless they’re gonna be mean to me about my skin color, then we’re gonna have a problem. ‘Cause I cannot stand racism at all. Back in Norfolk, there would be these kids that just would throw rocks on me and my brother for no reason. I don’t really feel that different unless you’re gonna single me out about it. But if it doesn’t come up at all, I just feel equal to everyone else.

I would like to go back to Sudan someday, ‘cause I want to learn more about it ‘cause I hardly know anything right now about it. I want to go back and remember this is where I was born. This is where I grew up, but the way that women are treated it’s like WRONG! ‘Cause the women are expected to do all the cleaning and just stay home, do everything, and they’re not given like hardly any rights, so it’s like I don’t want to go over there if they’re going to treat me like that. I would not handle it well. I would not. I would get mad easily, if you try to tell me to do something, I’m going to get mad. I was thinking of being a lawyer because I can see myself defending people if they’re accused, accused wrongly or something. Like, I can see myself defending people that are not treated right.

CELESTE PORTILLO (Lincoln)

A note to her ELL teacher, written during her break while working at Wendy’s: Hello. I just want to say that the quilt is beyond beautiful…. fantastic!!! I have no idea how these few words can offer up any more than scant reward for such a tremendous effort. I really enjoyed doing that specialty. I learn something new from it. Please know that I’m at my sincerest when I say that the generosity of spirit from everyone involved with the construction of this project of art has truly, truly touched me. I’m thankful, because I have to do this amazing project. And I just want to say thank you for the opportunity.

NOTE: “Celeste Portillo watched her grandmother in Guatemala use a sewing machine and make clothes. But for 15 years, she didn’t know her mother, who had moved to the U.S. She didn’t know her two younger brothers. She knew pain. While in Guatemala, Celeste’s father had hurt her. Celeste’s aunt noticed the fresh scars on her arms, and called Celeste’s mother. Mom came ‘home,’ Celeste met her mother for the first time since she was a young baby. Yet she had no hesitation to move to the States with her mom. Now Celeste is a senior and ELL student at Lincoln High School. She’s telling her story. One quilt block at a time.” — from a story by Lincoln Public Schools Communications.

RUTH KUPFER (Lincoln)

The most enduring outcome of The Quilted Conscience project in Lincoln was the affection that grew from the personal connections quilters and students made with one another. Beginning with touching first meetings and culminating with rich reconnections after the project had ended, relationships were nurtured as students told stories of their homeland and experiences in refugee camps and quilters opened their hearts and let go of assumptions.

As they worked on their memory blocks, the young people and the mature women compared notes on ways that their lives were different yet similar, from farming methods to food preparation to the realization of dreams. One young man wanted to bring his mentor home to cook a meal for her to demonstrate the skills he’d gained from being, as the eldest, his family’s primary chef. All the students were anxious to find ways like this to validate their stories for these new friends.

When the project participants reunited several months after the end of their work together, the young people were excited and anxious to see their mentors again and to give them updates about the realization of their dreams. One young man had changed his plans from being a mechanic to being a college student; a young woman who had wanted to be a nurse reported that she was on the path to becoming a doctor. Seeing students on the cusp of adulthood brought even more depth to the quilters’ understanding of what it means to be an immigrant/ refugee. Many grateful women said that participating in The Quilted Conscience program was one of the best experiences they’d ever had.

As for me, being the Quilt Coordinator of the Lincoln High School Quilted Conscience project enabled me to experience again the honor it was to work with immigrant students as I had throughout my 35-year career teaching in public schools. Witnessing these students’ graceful storytelling and enthusiastic creativity reminded me how important their contributions are to our community. I am also grateful to be part of such a rich quilting community here in Nebraska, from whom I could invite such talented and compassionate women to become mentors for this important project.

![]()

SUSAN HERTZLER (Lincoln)

As an ELL educator for 17 years I have learned so much about the world through the eyes, ears, and hearts of my students. Some of their stories have been heartbreaking, some funny, and others uplifting. Above all, there has always been a common thread of family throughout their stories and almost always these stories cannot find their way out of my head.

Over the years, without even realizing it, I have been searching for a way to more concretely share some of these stories with those outside the halls of my school. I felt guilty for keeping them to myself. When I learned about TQC I knew immediately that it would be a perfect way to get those stories into the hearts and minds of others. From the beginning, TQC was a labor of love. I was used to working with my ELL students every day, but when the project began I was reminded of the path that I myself had taken all those years ago in learning about different cultures. I witnessed the mature quilters who had volunteered to work with the students as their eyes widened upon hearing some of the tragic situations that many were illustrating in their memory blocks. I could see the power of hearing these firsthand accounts; they were obviously moved. As the project wound down I could see that it was going to be tough for the quilters to say goodbye to the students.

The quilt is a way for the quilters, as well as others, to have endless opportunities to experience and re-experience the memories and the dreams of these young immigrants. The ripple effect cannot be measured and I feel proud to have been a part of it. Hopefully TQC, and other projects like this, can continue be offered in the future–Life Changing!

TRACY MORROW (Grand Island)

I’m a Newcomers teacher here in Grand Island, Nebraska. So I teach students who are new to America from all across the world. TQC gave me the opportunity to learn about my Sudanese immigrant students and how they have evolved into American young women of today. But even more importantly I have learned so much from the students that I work with today, and I have adopted and modified this program as a yearly opportunity for each of the immigrant students new to the U.S. and to the English language to share their stories with our schools, our community, and the public at the Nebraska State Fair. I have learned so much from their memories of their homeland and I will continue to embrace the students and their stories from their homeland.

The Social Studies Department at Barr Middle School was planning a World History Day when the entire school would circulate from room to room for programs developed by students and their teachers. I was asked to share the Sudanese students’ work and experiences from The Quilted Conscience program. I had the girls share some life experiences from the Sudan….how the girls are named in their country was especially interesting! They sang some traditional songs, discussed foods, as well as other aspects of their daily life. Our presentation was voted the favorite learning room of the day!

As a result of World History Day, the girls felt a pride of accomplishment, were much more integrated at school, and the acceptance by other students increased dramatically. I heard many comments such as “Congratulations!” and “Thanks for sharing!” The local newspaper featured several front page clips that followed the Quilted Conscience project, which added to the acceptance and integration of the Sudanese students.

I retired from teaching and moved to Lincoln with my husband. I treasure this Quilted Conscience experience and the team involved. Peggie Hartwell (TQC’s artistic advisor) and I have become close friends and she comes each summer to spend several days at our home. We have both been involved with Quilted Conscience quilts being made in Lincoln and in Omaha with the Karen refugee students. One of the original Sudanese students, Nyakim, of the first project in Grand Island, has moved to Lincoln now, too. She asked Peggie and me to go to her church one Sunday last year. That is a treasured memory.

Project Director, JOHN SORENSEN (New York City/Grand Island)

TQC, as it develops, brings forth many important observations and questions from partners and colleagues. One topic is “Do workshops like this reinforce a tendency teachers and community members have to see immigrant outreach and support as a process of assimilation?”

Another interesting point found in the comments from TQC quilters and advisors is how some partners speak of how they could “relate” to the cultures from which the students have come. One analyst found these comments to be “startling” and asked, “What to make of that? What does ‘relate’ really mean?” My thoughts are that the quilters and advisors simply mean that they have had certain life experiences that are somewhat similar to those of the students. Some of those local partners grew up in rural or economically disadvantaged areas where they had to walk long distances to get clean water, and where they did not have electricity or plumbing. I think they are relating to a shared experience of living a rural life, working with cattle, things of that sort. The quilters and advisors are very aware that the students had experienced traumas far beyond any that they have known.

In the wider political context of our current historical moment, new questions are asked. “Will these workshops continue? What does it mean for quilters and participants that immigrants may have an even harder time coming to the U.S.? Has the unity and community been disrupted or impacted by the national context?” These are important issues worthy of extensive consideration and analysis in their own right. For now I will simply note that, yes, the workshops are continuing, and I hope that in future community discussions and via online forums these key questions, along with additional assessment of the program goals, will form the basis for careful analysis to inform the ways TQC responds to and engages with the ever-unfolding political environment in the United States of America, our “Nation of Immigrants.”

Parent, YAUNIS ANDINDI ( Grand Island) Statement accompanying his “Life in Sudan” photo essay for TQC exhibitions:

My name is Yaunis Andindi. I am from Rikefi village (2,000 people) in the Nuba Mountains of South Central Sudan. I was born in 1974, I think. But no records were kept, so I am not sure. I have ten brothers and sisters. The life was a little hard in my village, which is normal, we didn’t have electricity. The lights. We didn’t have those. We were using just the stars and a moon. When the moon come up, everybody’s happy because they have light now.

There was the civil war going on about over 20 years in our country. The soldiers from the Northern Sudan Army, they came several times–many times to destroy our village. And I decide to leave the country. I left my home village in 1999 because of the Civil War in Sudan. The Government was coming to destroy my village. The Government destroyed my village many times and my people would go to the mountains to hide. The life was hard. Then I decided to go to Egypt. It was difficult for me to escape–but I made it. Two years later, I went to the United Nations Refugee Office in Cairo and told them my story. They accepted me and offered for me to come to America. I lived in Minnesota for almost five years, working as a custodian at a Christian private school. Then I came to Grand Island in 2005 with my wife Simaya Cori and our little son Rams to be close to my cousin Yohana Adenti and to find a better life for my family. I work at Swift Company Meatpacking Plant and worship at the Methodist Church. My wife and I have a new daughter, Gina.

We are happy to be in America, but we still miss our country. You know, even if you’re born in a fire, you don’t want to lose your culture.

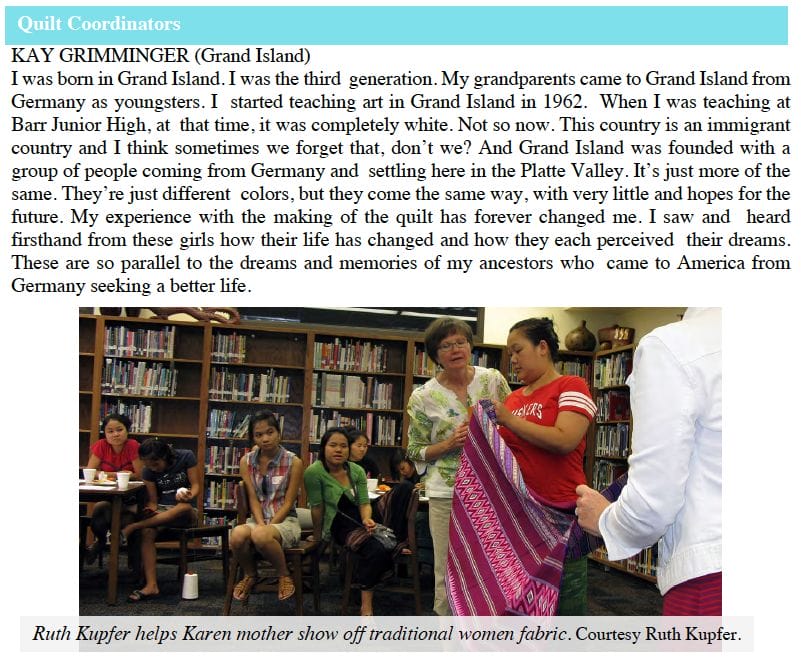

Community Partners

TAMMY MORRIS (Grand Island Community Foundation, Former CEO)

I attended an unveiling of a Dreams and Memories quilt in Omaha and can still remember the smiles on the students’ faces and the pride they had in their quilt. They shared sometimes painful memories of their upbringing, but their faces lit up when they spoke of the quilted square that reflected their dreams. They told of how their dreams were much greater now that they saw the opportunity and promise ahead of them. I remember them sharing also their traditional dance and [how] they took pride in their home country. I have seen this project in multiple communities and admired how it brought people together and increased community engagement across various cultures and backgrounds. This is a project that transcends gender, race, and culture and goes down to the core of one single human race.

KATHY STEINAUER SMITH (Woods Charitable Fund, Community Investment Director, Lincoln)

The Quilted Conscience brings together people across generations and cultural backgrounds to share their stories, to build trust in one another, and to learn from the others’ experiences. WCF saw a unique opportunity in TQC to support an educational project that, through art and creative storytelling, encourages our community to make connections with Lincoln’s New Americans. We could see the affection and trust that developed between the students and the quilters, and we are not surprised that other communities and schools see the great potential in The Quilted Conscience as a way to build this rapport and these relationships.

MARY YAGER (Humanities Nebraska, Associate Director, Lincoln)

Every now and then a project comes along that just seems to take on a life of its own. The Quilted Conscience is such a project! Humanities Nebraska points to The Quilted Conscience project as an example of an investment of its grants funds that has evolved and developed over a period of time and that, because of diverse collaborations, has become much more than it could otherwise have been. Sometimes it’s a matter of timing, too. The Quilted Conscience project came along at the right time for Humanities Nebraska, which had launched a New Nebraskans initiative. The initiative and the project dovetailed nicely. Requests from a growing number of groups in Nebraska, other states, and even other countries to replicate this project led to the production of curriculum materials and creation of a website (also HN funded) to allow groups in any location to use The Quilted Conscience workshop template and film to host their own projects. The growth has been a joy to see!

Media Partner

CHRISTINE LESIAK (NET Television Producer, Lincoln)

On an unusually warm afternoon in March 2017, I took a walk to the International Quilt Center in Lincoln. It was the last day of the quilt workshop, inspired by John Sorensen’s film, The Quilted Conscience, and since the TV station where I work is just a block away, there was no excuse not to check it out. The students were cutting fabric for their designs—their dreams and memories— for a new quilt. They come from the troubled places all over the world—Iraq, Burma, Thailand, Venezuela, Guatemala, Democratic Republic of Congo. One of the volunteers told me she had heard stories so violent she could hardly bear it. But as the students quietly worked away I had just one thought—they’re safe here now.

Artistic Advisor

PEGGIE HARTWELL (Charleston, SC)

I was born in Springfield, South Carolina, and I grew up around quilters. When I got on the plane to go to Nebraska, I didn’t know what to expect. I couldn’t imagine because this was the first time that I was going to be working with Sudanese children. So I went there saying, I’m going to show them all my techniques. And I’m going to teach them this and teach them that. But in the end, as always, I became the student. When I look at those girls, I know that everything is possible. To stand in front of their quilt was unbelievable because for the first time, they were able to see their voice on cloth. They were able to see in the complete form those blocks that they had created.

They were able to see it as a continuation of their hope.

Peggie Hartwell with Sudanese American student.

Photo courtesy The Grand Island Independent / Scott Kingsley.

Conclusion

The Quilted Conscience is an ever-evolving project. In its earliest stages, it was a simple arts education program to facilitate the making of a film that would give contemporary form to the ideals and vision of social justice pioneer Grace Abbott’s work with and for the children, immigrants, and women of the U.S. There was no thought that our first workshop would be any more than an event focused on the experience of a specific group of female refugee children in Abbott’s hometown of Grand Island. But even before the filming was completed, requests came (initially from artistic advisor Peggie Hartwell’s home area of Charleston, South Carolina, and Grand Island ELL Coordinator Tracy Morrow) to replicate TQC workshops and exhibitions in their communities. Since then, the project has regularly received similar requests, mostly in Nebraska, but also from across the U.S.

With each new TQC event, fresh ideas and approaches develop through engagement with new students, quilters, educators, and communities. At the beginning, TQC was focused on the idea of “contrasts and connections.” We recognized the strong differences between the immigrant or refugee students and the American quilters, while at the same time exploring ways these diverse groups might come to see that they have more fundamental experiences in common than they might at first think, and that this commonality is an opportunity to form positive new community bonds and even friendships.

Slowly, however, a new vision came into our work: the idea of student agency. This wasn’t, at first, a conscious choice, but an organic development, put forward primarily through the creative works of the student artists. For example, at a recent TQC exhibition, a student artist (a young Yazidi man) addressed the audience. Showing his memory block concerning the destruction of his home village, he made a strong point that he had created this block to let people know that his village did not exist anymore, it had been completely destroyed. The feeling in what he said was that, by making this image, he was bringing his village back into existence, through his artwork, he was reclaiming his past and making it live again, for himself and his new neighbors.

Finally, by its nature, TQC is an evolutionary project in terms of simple attitudes. Public and personal opinions, even prejudices, may best be changed through experiential means, and patient, persistent actions. One priority is to encourage people (both locals and newcomers) to “open their minds” about “the other.” For example, I think many project partners begin participation by seeing TQC as a way to help others … and I feel that this is a healthy, very human way to start. But, as Peggie Hartwell notes, although she came to Nebraska thinking that she was on her way to “help” the Sudanese students, in the end she came to see how much they had helped her; how much she and they had helped one another.

The project began with a simple focus, but as the workshops have evolved we recognize and embrace the idea of strengthening the cultural identities of the students. I see this as a major goal for future work. Looking back over the past decade, I think of the passage from the Tao te Ching: “The longest journey begins with a single step.”’ Or, to quote again our project inspiration, Grace Abbott:

Doing the next thing, and making good at it, has this certain advantage: You can never tell what it is going to lead to, or what new and possibly thrilling experience is lying in wait just around the corner.

— Grace Abbott, 1926

John Sorensen is director and creator of The Quilted Conscience workshops and the Abbott Sisters Project. His film work as writer/director includes The Quilted Conscience and The Andy Warhol Robot. For Public Radio he has written and directed dramatic works and is founding director of the New York Public Library’s Four Corners world culture series. His most recent books are The Mystical Filmmaker (with Peter Whitehead, 2015) and A Sister’s Memories, the story of social justice pioneer Grace Abbott (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

URLS

Lincoln Public Schools Communications https://www.lps.org/post/detail.cfm?id=11732

The Quilted Conscience http://thequiltedconscience.org

The “How To” Handbook http://thequiltedconscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/TQC_handbook.pdf

Works Cited

Abbott, Grace. 1926, July 31. From the Edith and Grace Abbott Papers, University of Chicago Library.

—. 1934. “A New Horizon for Children in the Post-Depression Period,” an address on “The Economic Basis of Child Welfare,” delivered at the commencement exercises of the New Jersey College for Women.

Sorensen, John, with Judith Sealander. 2008. The Grace Abbott Reader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.